Just to say that I am active on both my Facebook Author Page and Instagram.

I also now have a series of posts called “Breast Cancer is One Way to Look at Things” on Medium, with the same posts on Substack.

My most recent nonfiction is What Walks This Way: Discovering the Wildlife Around Us Through Their Tracks and Signs (Columbia University Press, August, 2024) which has won the 2025 New Mexico Book Award in Nature/Environment. You can find What Walks This Way at an online bookstore like Amazon or Indiebound. I have also been doing workshops and presentations related to wildlife tracking. Feel free to contact me.

“Sharman Apt Russell brings a tracker’s eye to the lives of wild animals, illuminating signs she finds with a curated wealth of natural history. With language as clear as fresh deer tracks in snow, she answers the important questions: why skunks are striped, how to tell coyote prints from a dog’s, and what drives a species toward or away from extinction. Readers who rarely look at the ground will have a hard time looking back up, and those familiar with tracking will be surprised by what they learn.”—Craig Childs, author of Stone Desert

“Far more than a field guide, What Walks This Way captures the wonder and delight of following our fellow animals.”—Michelle Nijhuis, author of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

“As someone who dreams about the wildlife crisscrossing my neighborhood—and the continent—What Walks This Way is the marvelous book I have been waiting for. Russell’s lucid and engaging voice helps us decipher wildlife tracks while greatly enriching our lexicon of the natural world.”—Priyanka Kumar, author of Conversations with Birds

Consider trying out the new Shepherd’s site with reading recommendations on all topics. Here are five books that I recommend on connecting to wild animals.

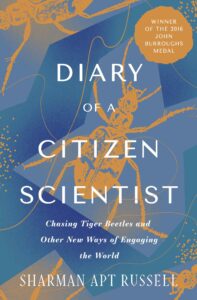

Four of my books have been reissued by Open Road Integrated Media. They are regularly being offered at special promotion rates. The Last Matriarch is a novel set some 11,000 years ago about the extinction of the Pleistocene mammoths. When the Land was Young: Reflections on American Archaeology has a few chapters on those extinctions. My first collection of essays, Songs of the Fluteplayer: Seasons of Life in the Southwest, hearkens back to the 1980s and being a back-to-the-lander: homebirths, a too big garden, too many goats, trying to root into soil like a potato or carrot. Finally, Diary of a Citizen Scientist: Chasing Tiger Beetles and Other New Ways of Engaging with the World is self-explanatory. Tiger beetles! I’m glad to have new publishers and glad they are doing this.

WildEarth Guardians has produced a new anthology, First and Wildest: The Gila Wilderness at 100 (Torrey House Press, 2022). They also made some impressive videos. This one is quite short. This one is longer. Beautiful images of the Gila Wilderness and Gila National Forest! And here is a nice review. I’m proud to be part of this work.

My nonfiction Within Our Grasp: Childhood Malnutrition Worldwide and the Revolution Taking Place to End It took a long time to write and publish. Pantheon released the book April, 2021. The delay allowed me to include the 2020 pandemic and its effects on hunger around the world. Although much has changed in the last few years, notably the defunding of USAID, I found a lot of wonder, hope, and inspiration in this subject.

Wonder—the miracle of the body, how we turn food and nutrients, metals and molecules, into who we are. Into thought and story and love. The wonder of vitamins and minerals. How we are made from the Earth.

Inspiration—so many people in the world working to feed the children of the world. We can marvel at the harm we do each other, since so much human suffering is caused by other humans. Or we can marvel at the compassion we have for each other, for the body of humans on this Earth that is our body, too.

Hope—we now have the knowledge, means, and motivation to end childhood malnutrition and stunting. This would have enormous economic and environmental rewards. This, really, is within our grasp.

To order from Amazon: Within Our Grasp: Childhood Malnutrition Worldwide and the Revolution Taking Place to End It

To get the audio at Audible.

To order any of my books from an independent bookstore: Indie Rocks.

I remain so pleased that Diary of a Citizen Scientist: Chasing Tiger Beetles and Other New Ways of Engaging with the World (Oregon State University Press, 2014) was given the 2016 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Natural History Writing.

I remain so pleased that Diary of a Citizen Scientist: Chasing Tiger Beetles and Other New Ways of Engaging with the World (Oregon State University Press, 2014) was given the 2016 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Natural History Writing.

From the announcement: “The John Burroughs Medal was created in 1924 to recognize the best in nature writing and to honor the literary legacy of naturalist John Burroughs. The Medal has been awarded annually to a distinguished book of nature writing that combines scientific accuracy, firsthand fieldwork, and excellent natural history writing. This year’s winner was selected by a review committee of Medal recipients. Past Burroughs Medalists include Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, Joseph Wood Krutch, Loren Eiseley, Roger Tory Peterson, John Hay, Peter Matthiessen, John McPhee, Ann Zwinger, Barry Lopez, Gary Nabhan, Robert Michael Pyle, Richard Nelson, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Franklin Burroughs, Edward Hoagland, Kathleen Jamie, and Sherry Simpson.”

Well, to be in such a list.

***

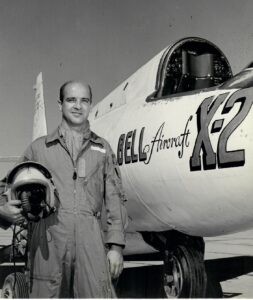

This year I signed a contract with the University of New Mexico Press to publish The Desert Dreams of Flying to the Moon. You might call this a resurrection, of a particular kind of joyfulness and courage, in a particular time and place. Wars and science play their part as I follow the lives of three men: Glen Edwards, Milburn Grant Apt, and Neil Armstrong. My childhood threads their stories, although this is less my memoir than my father’s, those halcyon years of the 1940s and 1950s, cloudscapes and rocket planes. I wrote this out of something that happened to me which I have long thought unusual but which I now see as common, manifested in many forms.

People live inside us. Sometimes they live in the darkness of the body with its opaque interior, synapses and nerves, and their emergence is from that darkness. Sometimes they appear in hallucinatory color, as if on another planet or dimension, walking under a cerulean sky. For as long as I can remember, my father has lived inside me, a short man, slight, bald, with a shy smile. We never spoke to each other, except for once when I was middle-aged—and that proved to be a misunderstanding. For most of my life, he has been a presence more than a personality. I wrote The Desert Dreams out of that presence and, if you are willing to go a little deeper into the mythology we shape into a life, out of the animate desert where I was born and where I live today, out of the curiosity we have for the world and the world for us.

In this book, I am also talking to my father, and he to me, about what has happened on this Earth in the 64 years since he died. These are the conversations that interest me the most.

Chapter One: The Desert Dreams of Flying to the Moon

I am watching a YouTube video of my father’s death. The film was made by the United States Air Force in 1956 and declassified more than fifty years later so I can see it now on my computer screen at home. The heavy B-50 flies through the gray-toned sky before releasing the small experimental X-2, designed to glide until its rocket engines power, explode, and push the plane forward. Silently, without music or narration, the X-2 flashes into the distance, sleek with pointed nose and swept-back wings, faster, faster, over three times the speed of sound, faster than any human being has flown before. At the end of this test flight, the X-2 is meant to glide again, landing on a dry lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California. My father is the pilot. I stare at the vanishing plane with a frisson of knowledge, holding on to the moment before loss, and wanting to warn: Don’t go so fast today. I play with time, wanting to change time and knowing I would be changing myself, something I cannot really imagine. What would I be without a dead father?

Abruptly, the video shows footage from inside the cockpit, a camera there positioned to view the instrument panel. Here is the back of my father’s head. He is wearing a helmet, which moves jerkily across the screen as the X-2 becomes unstable, rolls, gyrates. No one knew this would happen. That’s why someone had to test the plane. Part of the screen, now half the screen, is a bright white light, irregular shapes of light fraught with meaning like an abstract piece of art. Everything on that canvas is significant, emotional, ineluctable. My father is being thrown about this tiny space filled with light. In seconds, he is jettisoning the cone of the plane which also serves as an escape capsule.

That’s the last I see of him. Rectangles, bright light, the back of a head. For the next twenty minutes of this video, the Air Force forensic team examine the debris on the ground. They pan over pieces of metal, a broken wing, the wreckage of the capsule. We see its dark interior. Thankfully, we don’t see much. Men take photographs. They stand around in groups of three, four, eight. These men are everywhere on the dry lakebed, some wearing white shirts and ties, some in uniforms, some carrying guns. They all seem somber, peering at crumpled metal, reaching in, pulling out wires. A boxy helicopter kicks up dust. Other helicopters come and go. The film records the departure of an ambulance-sized vehicle. More men trudge through sand, murmur, pick up something.

The Mojave Desert dwarfs this scene of hapless men. The filmmakers seemed to want to show that, too, these undulations of hills and mountains, layers of cinnamon-brown and chocolate-brown, sweeps of monotonous light-green creosote. This is the beauty of absence. The unadorned lift of granite and basalt. The empty sky, the empty desert.

But you and I know better. We know how the sky fills with high cirrus clouds, virga of moisture evaporating as it falls, great anvils of cumulonimbus. We know the scorpion and grasshopper mouse, the dove, the owl, the desert tortoise. We know because we are in love with this sky and this land. Even now, from the distance of another century, I can feel the sun’s heat on my arm. I can smell creosote, a mix of turpentine and lemon. I was two years old when my father crashed in the escape capsule of the X-2. I am seventy years old now. That span of time is nothing. A rustle of leaves. A flash of light in the corner of your eye.

My father was a Kansas farm boy. At first, the dry lakebed and bony horizon seemed as alien to him as the moon. Only slowly, almost reluctantly, did he grow to love the desert.

Always, of course, he loved the sky. In home movies of flying—the jerky blurred quality of 8-millimeter film—as a passenger in a cargo transport or in a nifty two-seater fighter plane, he took many images of the sky, those high clouds, that cerulean blue. In other movies of family vacations, he paused at the figures of his wife and two little girls, the wife so happy, the little girls like all little girls. Then he moved on to the sky, the architecture of a storm over Yellowstone National Park, the canyons of space at the Grand Canyon.

We see him most clearly in these choices. We see him pulling on his pressurized flight suit made for high altitude. “You’ve got this hacked, dad,” his chase pilot says in the slang of the day. Two chase planes will follow the experimental flight, offering advice by radio, monitoring parts of the X-2 that its pilot cannot see. By now, 9 a.m., the white research plane has been rolled under the belly of the B-50 and fitted into place. She is the most advanced aircraft of her day, only forty-five feet long, with a wingspan of thirty-four feet. So often, my father has leaned his shoulder against a wing, patted her flank. She looks friendly and lived in, scuffed from a few bumpy landings on the dry lakebed, paint peeling on contracted metal.

Up in the air, at 35,000 feet, in the cockpit of the B-50, we see him say goodbye to the pilot and co-pilot and start the crawl through the tunnel that runs above the plane’s bomb bay. We see him descend a ladder into the cockpit of the X-2, his shoulders wedged into this cramped space. His face is covered by the helmet and oxygen mask, so that all we see now are his blue eyes. We see him buckle his seatbelt. Someone in the B-50 closes the canopy over his head.

There is a long list of things to do—check pump number eleven, open drain switch, retract air scoops—and then the countdown. Five, four, three, two, one, drop away. There are years of training and the possibility they will all end now. Test pilots died at the rate of one a week in the heyday 1950s. The motto of those test pilots was Ad explorata: into the unknown. In the drumbeat of preparing the X-2 for flight, humming along with the professionalism of the crew, there is always that. The pursuit of revelation. Into the unknown.

As for the people my father left behind, we will fashion our own beauty and meaning from those accumulated moments. Kiss your wife goodbye, climb into the cockpit, fly over the Earth faster than any human being has flown before, eject the escape capsule, hit the ground. My sister dreams that he returns to her a few days later. Sitting on her bed that night, he tells her everything will be okay. Okay is what the five-year-old hears. In my crib nearby, I am dreaming, too. Outside our window, the desert is dreaming. In the small trim houses and dormitories and hospital at Edwards Air Force Base, the soldiers and pilots and mechanics and administrators and doctors and nurses and their families are dreaming. All of us, dreaming and flying.